Perched next to stately Westminster Abbey—site of coronations, royal weddings, and funerals for hundreds of years—sits her humble little sister, the Church of St. Margaret. While Westminster Abbey is “the Queen’s Church,” St. Margaret’s is the church of the House of Commons. Sometimes called “the church on Parliament Square,” it stands across from the gilded gates of the Houses of Parliament, where police constable Keith Palmer was stabbed to death in a terrorist attack in 2017. Flowers, cards, and balloons still mark the spot daily. Members of Parliament have only to cross a busy street and fight their way through throngs of tourists and Brexit protestors to enter the quiet repose of their parish away from home. On the morning of June 2, 2019, I attended the Sung Eucharist at St. Margaret’s and thought about chains.

My friend Fiona, an Anglican priest who leads an innovative multifaith ministry at the financial hub of Canary Wharf, was preaching that morning. After I was seated, I found attached to the pew before me a slightly shabby red kneeling cushion with a striking portcullis motif embroidered in gold. The portcullis is the symbol of the House of Commons, and, as depicted at St. Margaret’s, includes two chains on either side of the gate that were used to raise or lower the portcullis quickly in times of attack. The kneeling cushion was connected to a bronze chain that was bolted firmly to the pew. Although the chain extended far enough for the cushion to reach the floor, it could not be moved far from its anchor. Were these well-worn cushions antiques, so valuable that the church feared that a brash American home decorator might decide to repurpose them? Or were the parish authorities worried that a homeless person might appropriate one to serve as a pillow for a weary head? The Order of Service that morning, after all, did recommend taking one’s handbag to the altar during the Eucharist to prevent theft.

St. Margaret’s was originally built in the late eleventh century to provide the Benedictine monks in residence at Westminster Abbey with some peace and quiet as they sang the Divine Office. Apparently, the common tradesmen and farmers of Westminster who attended daily Mass were disruptive, so the monks built a smaller church for the locals next to the grand Abbey edifice. By the end of the fifteenth century, St. Margaret’s was so dilapidated that it required almost a complete reconstruction. Additional restorations occurred during the eighteenth, nineteenth, and twentieth centuries, but today’s building is substantially the same as the one consecrated in 1523.

With Henry VIII’s dissolution of the monasteries in 1540, Westminster Abbey became a cathedral church, and in 1614, St. Margaret’s was declared the parish church of the Parliament because the then-influential Puritans found the liturgical worship of the Abbey excessively ornate. Since 1681, the front pew across from the lectern has been reserved for the Speaker of the House of Commons. John Milton, the great Puritan poet and civil servant, was a parishioner at St. Margaret’s and married and buried his second wife there. A Victorian stained glass window in the north aisle, donated by an American admirer, depicts scenes from Milton’s life and poetry. Winston Churchill was married at St. Margaret’s, and at the conclusion of World War II he brought the entire House of Commons there for a thanksgiving service.

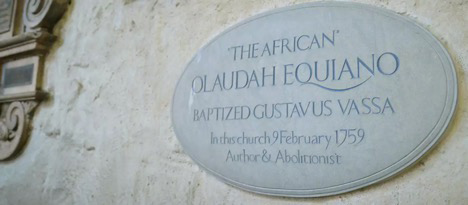

Among the many monuments—including the tomb of Sir Walter Raleigh and a charming memorial to Queen Elizabeth I’s nursemaid—the one I found the most moving was a simple white marble oval plaque dedicated to Olaudah Equiano, placed near the font. One of the first Africans to chronicle his life in the chains of slavery, Equiano’s 1789 memoir (The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vasa, the African) powerfully depicts the barbarity of the slave trade. Equiano was captured in Africa at the age of eleven and subsequently was sold numerous times both in England and America. When he converted to Christianity in 1759, his “owner” permitted him to be baptized at St. Margaret’s under his slave name: Gustavus Vasa. Like another well-known former slave, Frederick Douglass, Equiano scraped together an education to free his mind from the chains of ignorance, learning to read and write with the help of British sailors. Assisted by a Quaker “owner,” he eventually made enough money to buy his freedom in 1768. Equiano’s influential memoir and stirring speeches for a black abolitionist group played an important role in the eventual ending of the slave trade in Britain in 1820.

More slaves and chains showed up in the scripture reading that morning, which was from Acts 16. Paul and Silas are in Philippi being stalked by a slave girl with a spirit of divination, who earns a good profit for her “owners” with her fortune-telling skills. “These men are slaves of the Most High God, who proclaim to you a way of salvation,” she shouts on the streets. This goes on for days until Paul, “very much annoyed,” turns back and orders the spirit to leave her. Her displeased “owners,” deprived of their ill-begotten income, bring the two apostles before the authorities, who have them flogged, thrown into prison, and put in stocks. At midnight, Paul and Silas are praying and singing hymns when a violent earthquake shakes the prison, “and immediately all the doors were opened and everyone’s chains were unfastened.” The jailer prepares to kill himself because he assumes that the prisoners have fled, but Paul reassures him that they are still there. Convicted of God’s power and mercy, the jailer believes, and he and his household are baptized. He takes Paul and Silas into his home, washes their wounds, and gives them food. God’s power, manifested in nature, unfastens the prisoners’ manacles, but the chains of violence and hunger experienced by the apostles are sundered by the believing jailer. Paul and Silas are indeed “slaves of the most high,” but in those spiritual chains they find ultimate freedom.

The chains of a portcullis can imprison, protect, or free, depending on the context. Nonetheless, even as Equiano dreamt and worked for a day when enslaved Africans would be free from the chains of slavery, we must dream and work for a day when all earthly chains will be broken—even those on the red kneeling cushions at St. Margaret’s.

Susan VanZanten is the dean of Christ College, the honors college at Valparaiso University.